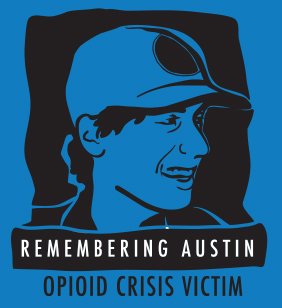

Opioids stole my son, Austin

A heartbreaking story from mother Tammy Chowdhury urging families to protect their children from the risk of opioid overdose:

I am writing to tell you how opioids stole my son Austin on June 9, 2017. He passed away from an accidental Fentanyl overdose at the age of 24. Austin was a beautiful person on the inside and out. He was openhearted and according to his friends he would do anything for them. He loved to travel, play basketball, and read. He would read two new books a month and told everyone to do the same. He couldn’t know or experience enough.

The worst day of my life was on June 9th of 2017 when we found our son unconscious on his bedroom floor. My husband and I attempted to revive him with CPR and mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, but he did not respond. We were in shock. How can this be? He was just talking, laughing, and watching a basketball game the night before. I felt like a piece of me died with him, my life will never be the same. What could I have done to stop this? I think of this every minute of every day, so maybe by sharing his story I can help others from going through what we have been going through since he passed away.

We believe Austin’s struggle with addiction began at age 14 with a dental procedure. Like normal, they gave him hydrocodone to ease the pain while he recuperated. A few months later I found leftover pills in his desk. I asked him if he was taking them, and he said he was. It seemed like idle, foolish experimentation. We threw the pills away and told him that abusing prescription medication was both dangerous and stupid. According to his school friends, not long after that he got involved with a group abusing prescription painkillers. The school expelled Austin and some of his friends when he was in 11th grade. There was no counseling, no opportunity to explain, no second chance. Immediately afterwards we took him to a psychiatrist for six weeks of counseling. These sessions failed to have any impact, and the day after they were completed, school security caught Austin buying pills during the school day. We were shocked into action and immediately took him to a rehabilitation center for an evaluation. Even with his repeated and reckless forays into pills, the evaluator said his use was merely recreational and not an immediate danger.

For the next year and a half he did well in school, and he was accepted to The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Austin was both academically and socially gifted, with a talent for delivering the message the listener wanted to hear—maybe that was part of the problem. His freshman and sophomore years were good, but in his junior year Austin moved into a house with a group of friends where they had frequent parties. This is not unusual for college students, and for those who are not predisposed to addiction, the impact may be negligible – like a few spills on the floor or a half-completed class assignment. For someone like Austin, for someone who craved artificial and chemical stimulation, the environment was toxic. According to his friends, he started taking pills and gradually began using heroin. We did not know he was doing either one at that time.

After completing his undergraduate degree, he decided to stay and complete a master’s degree. By his second year in grad school things started going downhill. We noticed he was spending a lot of money, but he always had a reason. He was earning his own money from working jobs at Starbucks, the student bookstore, a UNC research position, and Uber, but he always needed more. We attributed this to poor budgeting, to eating at restaurants, and from going out with his friends.

Now we see he had all the classic signs of addiction. Many days, he was moody, quiet and withdrawn—like he was somewhere else. Then one day he would be pleasant and chatty. In my gut I knew this was not normal. I would cry every time he was home because I knew this was not normal and something was very wrong. Things became worse when he started taking money from us when he was home. When we confronted him about it, he would say he owed money to his friends and that he probably smoked more weed than his friends. He claimed he only took pills every now and then. He was never honest.

We had many talks with Austin asking him to stop, but he always said he would and it wasn’t a big deal. He was doing well in school, so we thought if he had a serious problem it would have impacted his schoolwork. As parents we did not want to believe the worst could be happening, and based on what we knew—or what we thought we knew about addiction, we thought he would only be in serious danger if there was an obvious impact on his daily life. And as far as we could tell, he was functioning well. We had no idea he was doing heroin—if we had known we would have taken him out of school and got him the help he needed.

The last semester of grad school we wanted to take him out of school, but he thought it would be stupid since he was almost finished, and he promised he would stop. We also thought, he will be home soon and we will be able to keep an eye on him. On May12, 2017 Austin received his Master’s in Urban Planning from UNC Chapel Hill. He was so proud of his accomplishment. I think because he managed to get his Master’s with an addiction to heroin, Austin was a functional heroin user.

I feel I let my son down because all the signs were there. Sometimes, I think as parents we are subconsciously in denial because we just can’t believe our children are doing this. I was also uneducated about heroin addiction. I go through all the signs every day and all the what-ifs.

We found out Austin was doing heroin on June 7th. He was arrested for possession of heroin when he passed out at an intersection, behind the wheel of his car. Someone called the police and they found the heroin he had just bought but had not taken yet. He passed out because he was going through withdrawals. The next day we went to court, and he was with us all day. The next day we found Austin on his bedroom floor. What he likely believed was heroin was in fact two other drugs, Fentanyl and Cyclopropyl Fentanyl, a lethal mix. Fentanyl is a 100 times more potent than morphine and many times that of heroin. Approximately 125 people die every day from heroin overdoses mixed with Fentanyl. Later we found out someone brought this drug to him the night before he died.

I want readers to know two things. First, addiction is a biological, chronic brain disease. It is almost impossible to overcome an addiction without support and treatment. People do not become addicted to drugs or alcohol because of a failing of character or from a lack of willpower. They are predisposed to addiction, and once they are exposed to a drug, whatever it may be, they are tied to it chemically.

Second, that for those with addiction, their lives become disordered and disconnected from their healthy routines. As the addiction deepens, they stop caring for themselves properly, they become estranged from their friends and family, they stop taking pleasure in the ordinary pursuits that used to order their lives. After Austin passed away I found a notebook where he kept notes. He was seeing a counselor at Chapel Hill. I guess she told him two write down things for a successful day. These notes broke my heart: eat three healthy meals, get enough sleep, shower every day, keep in touch with friends. I just cried when I read this. I had no idea he was going through all this at school, because according to his roommate, when we came to see him he would clean up. Despite what was going on with Austin he would call us every Sunday, never missed a Sunday. Despite his addiction he was a good person with compassion and empathy for others.

I hope by telling Austin’s story I can stop one person thinking of trying that one pill, which may lead to heroin if you have an addictive predisposition. All it takes is one time. Why take the chance? It is like playing Russian roulette and it will not end well or quickly for the person with an addiction, for their family, or their community.

Every day is torture for my husband and me. We miss Austin so much and wonder what his life would have been if he had not gone down this road. If this story helps just one person then we will hopefully find peace. I know Austin would want us to do this. We do not want another family to go through this unbearable pain.

If you know someone is struggling with addiction, love them. Don’t fight them, don’t judge them and don’t throw them on the street. And for the love of everything holy, pray for them. They are hooked and helpless. Recovery is possible with love, support and treatments than in jail.

Let’s Talk Opioids with our family & friends to save lives.

I am writing to tell you how opioids stole my son Austin on June 9, 2017. He passed away from an accidental Fentanyl overdose at the age of 24. Austin was a beautiful person on the inside and out. He was openhearted and according to his friends he would do anything for them. He loved to travel, play basketball, and read. He would read two new books a month and told everyone to do the same. He couldn’t know or experience enough.

The worst day of my life was on June 9th of 2017 when we found our son unconscious on his bedroom floor. My husband and I attempted to revive him with CPR and mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, but he did not respond. We were in shock. How can this be? He was just talking, laughing, and watching a basketball game the night before. I felt like a piece of me died with him, my life will never be the same. What could I have done to stop this? I think of this every minute of every day, so maybe by sharing his story I can help others from going through what we have been going through since he passed away.

We believe Austin’s struggle with addiction began at age 14 with a dental procedure. Like normal, they gave him hydrocodone to ease the pain while he recuperated. A few months later I found leftover pills in his desk. I asked him if he was taking them, and he said he was. It seemed like idle, foolish experimentation. We threw the pills away and told him that abusing prescription medication was both dangerous and stupid. According to his school friends, not long after that he got involved with a group abusing prescription painkillers. The school expelled Austin and some of his friends when he was in 11th grade. There was no counseling, no opportunity to explain, no second chance. Immediately afterwards we took him to a psychiatrist for six weeks of counseling. These sessions failed to have any impact, and the day after they were completed, school security caught Austin buying pills during the school day. We were shocked into action and immediately took him to a rehabilitation center for an evaluation. Even with his repeated and reckless forays into pills, the evaluator said his use was merely recreational and not an immediate danger.

For the next year and a half he did well in school, and he was accepted to The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Austin was both academically and socially gifted, with a talent for delivering the message the listener wanted to hear—maybe that was part of the problem. His freshman and sophomore years were good, but in his junior year Austin moved into a house with a group of friends where they had frequent parties. This is not unusual for college students, and for those who are not predisposed to addiction, the impact may be negligible – like a few spills on the floor or a half-completed class assignment. For someone like Austin, for someone who craved artificial and chemical stimulation, the environment was toxic. According to his friends, he started taking pills and gradually began using heroin. We did not know he was doing either one at that time.

After completing his undergraduate degree, he decided to stay and complete a master’s degree. By his second year in grad school things started going downhill. We noticed he was spending a lot of money, but he always had a reason. He was earning his own money from working jobs at Starbucks, the student bookstore, a UNC research position, and Uber, but he always needed more. We attributed this to poor budgeting, to eating at restaurants, and from going out with his friends.

Now we see he had all the classic signs of addiction. Many days, he was moody, quiet and withdrawn—like he was somewhere else. Then one day he would be pleasant and chatty. In my gut I knew this was not normal. I would cry every time he was home because I knew this was not normal and something was very wrong. Things became worse when he started taking money from us when he was home. When we confronted him about it, he would say he owed money to his friends and that he probably smoked more weed than his friends. He claimed he only took pills every now and then. He was never honest.

We had many talks with Austin asking him to stop, but he always said he would and it wasn’t a big deal. He was doing well in school, so we thought if he had a serious problem it would have impacted his schoolwork. As parents we did not want to believe the worst could be happening, and based on what we knew—or what we thought we knew about addiction, we thought he would only be in serious danger if there was an obvious impact on his daily life. And as far as we could tell, he was functioning well. We had no idea he was doing heroin—if we had known we would have taken him out of school and got him the help he needed.

The last semester of grad school we wanted to take him out of school, but he thought it would be stupid since he was almost finished, and he promised he would stop. We also thought, he will be home soon and we will be able to keep an eye on him. On May12, 2017 Austin received his Master’s in Urban Planning from UNC Chapel Hill. He was so proud of his accomplishment. I think because he managed to get his Master’s with an addiction to heroin, Austin was a functional heroin user.

I feel I let my son down because all the signs were there. Sometimes, I think as parents we are subconsciously in denial because we just can’t believe our children are doing this. I was also uneducated about heroin addiction. I go through all the signs every day and all the what-ifs.

We found out Austin was doing heroin on June 7th. He was arrested for possession of heroin when he passed out at an intersection, behind the wheel of his car. Someone called the police and they found the heroin he had just bought but had not taken yet. He passed out because he was going through withdrawals. The next day we went to court, and he was with us all day. The next day we found Austin on his bedroom floor. What he likely believed was heroin was in fact two other drugs, Fentanyl and Cyclopropyl Fentanyl, a lethal mix. Fentanyl is a 100 times more potent than morphine and many times that of heroin. Approximately 125 people die every day from heroin overdoses mixed with Fentanyl. Later we found out someone brought this drug to him the night before he died.

I want readers to know two things. First, addiction is a biological, chronic brain disease. It is almost impossible to overcome an addiction without support and treatment. People do not become addicted to drugs or alcohol because of a failing of character or from a lack of willpower. They are predisposed to addiction, and once they are exposed to a drug, whatever it may be, they are tied to it chemically.

Second, that for those with addiction, their lives become disordered and disconnected from their healthy routines. As the addiction deepens, they stop caring for themselves properly, they become estranged from their friends and family, they stop taking pleasure in the ordinary pursuits that used to order their lives. After Austin passed away I found a notebook where he kept notes. He was seeing a counselor at Chapel Hill. I guess she told him two write down things for a successful day. These notes broke my heart: eat three healthy meals, get enough sleep, shower every day, keep in touch with friends. I just cried when I read this. I had no idea he was going through all this at school, because according to his roommate, when we came to see him he would clean up. Despite what was going on with Austin he would call us every Sunday, never missed a Sunday. Despite his addiction he was a good person with compassion and empathy for others.

I hope by telling Austin’s story I can stop one person thinking of trying that one pill, which may lead to heroin if you have an addictive predisposition. All it takes is one time. Why take the chance? It is like playing Russian roulette and it will not end well or quickly for the person with an addiction, for their family, or their community.

Every day is torture for my husband and me. We miss Austin so much and wonder what his life would have been if he had not gone down this road. If this story helps just one person then we will hopefully find peace. I know Austin would want us to do this. We do not want another family to go through this unbearable pain.

If you know someone is struggling with addiction, love them. Don’t fight them, don’t judge them and don’t throw them on the street. And for the love of everything holy, pray for them. They are hooked and helpless. Recovery is possible with love, support and treatments than in jail.

Let’s Talk Opioids with our family & friends to save lives.

My dad passed away in 2015 from a relapse. He was addicted to heroin since I was just 16. After getting sober and staying sober for a year, he and his wife were having issues in which after a big argument between the two of them one day it led him into relapsing.

I’ve talked to the dealer that sold him that fix. He apologized profusely and said “I couldn’t say no. I told him over and over that it was a bad idea and he shouldn’t… but you can’t say no to your dad. I only gave him a little bit and never expected to get that news the next day”

Part of his sobriety, he went to NA. In his class he had a book he wrote into. In the steps of his sobriety he was to apologize to people he’s hurt in his addiction. My grandpaw was listed. He wrote how he hurt him and how he would fix it. He followed through with what he wrote, and went to church with him on Easter Sunday.

Next on the list was me. He wrote how he’s hurt me and wrote that he would apologize to me for never being the father he could have been. He wrote that he would do this on April 12,2015.

That’s the morning he died.

It’s truly devestating and the feeling of defeat is unbearable. I am so sorry for your loss.